1. Okay, we've gotta know: any herbal connection between Four and Twenty and everybody's favorite seven-leaf clover? Cheech was asking.

I’m sorry to disappoint Cheech, but no. When I settled on the parameters of four lines and twenty words for the poems featured in the journal, I was thinking of those famous blackbirds baked in a pie. I’m a big fan of allusion, so I ran with it. I was aware that some readers would make an herbal connection, but I was just fine with that. Misinterpretation gives us greater exposure. Our hit count goes way up in April, and I know it’s not just because of National Poetry Month.

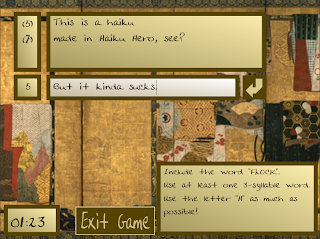

2. That's some seriously short poetry... just a hair's breadth above haiku. What is it about the short poems that you like?

As a reader, my favorite poems are ones that capture a moment in time and invite me to linger in that moment. Short form poetry does this well. The minimal space forces writers to make each word count, which can result in some potent poems. I also like how short form poems function like a box of assorted truffles when gathered together. Within the pages (or web pages) of a short form poetry journal, readers can taste both the deep, dark flavors of a poem packed with dense meaning and the strawberry cream goodness of a witty poem glazed with wordplay.

As a writer, I enjoy the challenge of saying something with as little filler as possible. A restricted word or syllable count prevents me from rambling. I’m an editor, so my favorite part of the writing process comes during the revision stage. Writing longer poetry delays my gratification. Short form poetry allows me to start slashing away at words much sooner.

As a poetry enthusiast, I like how the short form serves as ambassador to those who don’t like poetry. I’ve had several readers of Four and Twenty tell me that exposure to the journal has piqued their interest in poetry. Because readers don’t have to invest a lot of time into reading a short poem, they’re willing to give it a try. Quite often, they get hooked. Whenever I’m told that my journal has won over a previous poetry hater, I get all tingly and happy inside.

3. How often do you get submissions where the poet obviously didn't read the directions? Any particular methods of torture you want to put these people through?

I get multiple submissions in every monthly batch that far exceed our parameters. I’m always baffled by this. After all, the name of the journal is a clue to the length of the poems we publish. What gets me most is when authors use our online submission form to transgress the guidelines. I buried the link in the middle of the submissions page. To get to it without reading the directions, authors have to work really hard.

I sometimes think authors violate the guidelines on purpose, just so they can whine about being rejected and gain sympathy from their friends. When an author starts complaining to me about how no one understands their genius, I immediately ask if they’re following the submission guidelines when they send out their work. If the answer is no, they get “The Lecture.”

I have many ideas for ways to torture submission guideline offenders, many involving a locked room, Rick Astley, and a unitard. What I end up doing, though, is sending a rejection letter and then mocking the offender (anonymously) on my Facebook page. This usually involves a status update to the effect of “Vinnie Kinsella thanks you for the lovely sonnet you wrote for him, Unnamed Poet. It was obviously your intention to share it exclusively with him. Otherwise, you would have submitted it to someone who could have published it.”

4. Though authors are not limited to formal poetry, you mention in the submission guidelines a few forms other than haiku (senryu, sapphic, and tanaga) that will fit under the limit. Senryu are probably a better name for what we have going on at High Coup Journal; could you explain the other two briefly?

Tanaga, like haiku and senryu, is based on syllable count, but adds rhyme scheme into the mix. Tanaga contains four, seven-syllable lines. The end of each line follows a set rhyme scheme, such as AAAA or ABAB. Tanaga provides an added challenge for writers who prefer writing fixed form poetry.

Sapphic poems, named after the Greek poet Sappho, are based on meter. They are made up of four-line stanzas and follow a strict pattern of meter made up of trochees and dactyls. There is no limit to the number of stanzas a sapphic can contain, so a one-stanza sapphic could work as a Four and Twenty. However, it would be difficult to pull off in twenty words or fewer. A sapphic-based Four and Twenty would have to have a lot of polysyllabic words in it.

Since we’re on the topic of form, I would like to make a request. I’m always on the lookout for a Four and Twenty palindrome to leap out of the submission pool and scream, “Publish me!” Nobody sends me palindromes, and I like them. Please, send me a palindrome. Or at very least, send me a poem with a palindromic line or two in it.

5. Both your submissions page and your FAQ reflect an interest in the needs of younger readers (and their parents). How can we get young people interested in poetry?

To start, poetry needs to be taught in its proper context. There is this pervasive notion that all poems are stuffed with hidden meanings just waiting to be discovered. Teachers forget (or perhaps don’t even realize) that poetry is best introduced in musical terms, not literary terms. It’s perfectly acceptable for someone to like a song with nonsensical lyrics if the tune itself is compelling. Children aren’t asked by teachers to explain what is meant by the phrase “EE-I-EE-I-O” when they sing about Old McDonald. It’s understood that the phrase has musical meaning, but not any literary meaning. Poems, especially those following set patterns of meter and rhyme, have lots of phrases that make sense only in the context of music. If we allow children to first appreciate the feel of a poem without insisting they “get” the poem, we allow them to immerse themselves in poetry. After the immersion, they will naturally find meaning in what they read. If we push them to search for meaning in poetry, they will inevitably come up short and declare, “I don’t get poetry,” writing it off forever.

I also think it’s important for young readers to be exposed to poetry off the page. Poetry comes alive when we hear someone read it aloud. My freshman year of college, I had an English professor who was also a Shakespearean actor. He had memorized just about every poem in our poetry textbook. He would recite a poem for us at the top of each class. His performances compelled me to read poetry in ways none of my elementary, junior high, or high school teachers ever did. He made me fall in love with poems I previously hated reading when I was in high school. Children would benefit from such exposure to poetic passion. Whatever we can do to show young readers that poetry can be lively and engaging, I’m all for it. At very least, parents should be reading Shell Silverstein to their kids. I mean, come on, his poem about the sharp-tooth snail that will bite of your finger if you pick your nose is straight-up poetic genius! Inside everybody’s nose / There lives a sharp-tooth snail…

VINNIE KINSELLA's life revolves around words. In addition to being the publisher of Four and Twenty, he is a freelance book editor and an instructor in the Master’s in Writing program at Portland State University. He is also an avid Facebook status updater. His poetry can be found at vinniekinsella.com.